Part 1 from the book «ERZURUM (GARIN): ITS ARMENIAN HISTORY AND TRADITIONS» by Hratch A. Tarbassian. Translated from the Armenian by Nigol Schahgaldian. Published by The Garin Compatriotic Union of the United States, 1975.

Pages 13-21

PART ONE

CHAPTER I

UPPER ARMENIA OR THE PROVINCE OF GARIN (ERZURUM)

From earliest historical times, the Armenian plateau has been a land bridge connecting Europe with Asia and Africa, and as such, it has served as a battleground for the cultural, political, and military forces of the three continents.

The section of the Armenian homeland called Greater Armenia consisted of fifteen provinces among which the foremost position was occupied by Upper Armenia. The latter was bounded by Daik’, Ararat, Daron-Duruperan, Fourth Armenia, and Vasburagan. The province of Garin (Erzurum) was subdivided into Taranagh, Aryudz, Mgntzur, Pasen, Yegeghyats, Mananagh, Derjan, Sber, Shaghagomk’ (Torfum), and Garin. Conquered and devastated throughout centuries by foreign invaders from the East and West, Upper Armenia ultimately fell under the heavy yoke of the Ottoman Turks early in the sixteenth century. Thereafter, it became the center of the viceroyalty of the Eastern Provinces of Turkey and was referred to asErmenisdan Vilayefi. Its boundaries were often changed by the addition or subtraction of territories belonging to adjacent provinces for the sole purpose of preventing the Armenians from constituting a majority among the local inhabitants.

However, in 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, the vilayet of Erzurum was still the largest of the Turkish Eastern Provinces, consisting of an area of 76,000 square kilometers. It was bounded by Iran and the Caucasus on the east and northeast, by the provinces of Van, Bitlis (Paghesh), Diyarbeldr (Dikranagerd), and Harplit’CMamuret’-al-Aziz) on the south, Sepasdia (Sivaz, Sivas) on

13

west, and Drabizon (Trebizond) on the north.

The provincial administration of Erzurum encompassed Garin s» (Ovajek), Upper Pasen, Shaghagomk’ (Tbrfum), Kfeghi (Geghi), Khenus, Papert (Baiburt), Yegeghyat’s Kavar (Erzingyan), Gisgim, Sber (Isbir), and Bayazid. Its large meadows and well-watered pas- ture lands led ancient historians and geographers to call this province the «bosom» of the earth. Its rivers, and rivulets, with their full, rapid flow would have offered an inexhaustible source of electric power. *

Four great rivers had their source in this region: the Euphrates to the west, Araxes to the east, Jorokh (£oruh) to the north, and the Tigris, (Kayl) to the south. It was the land of magnificent waterfalls, the best known of which were Torfum Falls and the famous Kochkochan, formed by a rivulet plunging down from St. Illuminator’s Monastery (Armenian) to the nearby village of Mudurga. x

It was rich in mineral resources such as metals,1 coal, oil, clay, rock salt, and building rocks. Mineral springs2 added to the region’s considerable natural wealth, which in some cases was exploited and in others was left untouched. The wildlife of the region was represented by wolves, foxes, rabbits, wild boars, and reindeer as well as a wide variety of fish and birds.

The province, like nearby volcanic regions, has from ancient times been subject to tremors of different intensities. As a result of the earthquake of October 25, 1901, inhabitants of Garin were obliged to live in the streets and in tents for several months.

The population of the province was heterogeneous, consisting mainly of Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and several other minorities. v

The natives were the Armenians, the others being settlers of a later era.

1 For a detailed account of the mineral resources of Upper Armenia, see Hagop A. Kharajian, Hank’er Hayasdani, Potter Asia yev Giligio, pp. 23,

42-43, 49, 57. The defile of the so-called Gaydzagi Tzor (Valley of Lightning),

located on the road from Erzurum to St. Illuminator’s Monastery, contains open strata of coal which is be ing extracted today to meet the needs of the urban population of Erzurum. The villagers thought that the coal found there represented stones turned black from flashes of lightning.

Hence, the name «Valley of Lightning.»

2 Situated on the outskirts of Erzurum, the town of Ilije(or Ilija) is historically famous for its many mineral springs containing sulphur, iron and mineral

14

salts. The so-called Gelin Geldi (the Bride Came) mineral springs, located on a hillside near Ilije, bubbles and stops alternately. It is said that it receives its name from the fact that it bubbles more vigorously when new brides visit it. Another warm spring, Variant Tjermug of Aghdaghd, is also known to most Gariners for its yellow waters. To the south, there is yet another—Sev Tjermug—with its blackish waters. Another nearby spring, called T*etu Tjur, is noted for its acidic water, which is bottled and sent to many places. The cold spring called For in the village of Hintzk’, is rich in mineral salts and well-known for its curative qualities. In the village of Mudurga is found Zhamgochi Tjermug, which is surrounded by a nitrous soil that is sent to Erzurum. Its primary use is as a warm absorbent between two layers of infants’ diapers. Sogh Tjermug is another cold mineral spring named after the village where it is located. The Ghffzel Kiigh spring, located in a Turkish village of the same name, has a warm reddish water useful in healing rheumatism. The famous warm spring of the village ofShSkhnots, close to St. Yeprianos, was shut down by the Turkish government on the pretext that it was a trouble spot for the villagers on Gana Deri pilgrimage days. There were many other mineral springs in the Khachap’ayd mountains, where the northern branch of the Euphrates has its source.

15

CHAPTER II

THE ORIGIN AND LOCATION OF GARIN

This bountiful town of Garin

Built in the days of old

By the hands ofGaren our king,

The ruler of our fold.

—Traditional

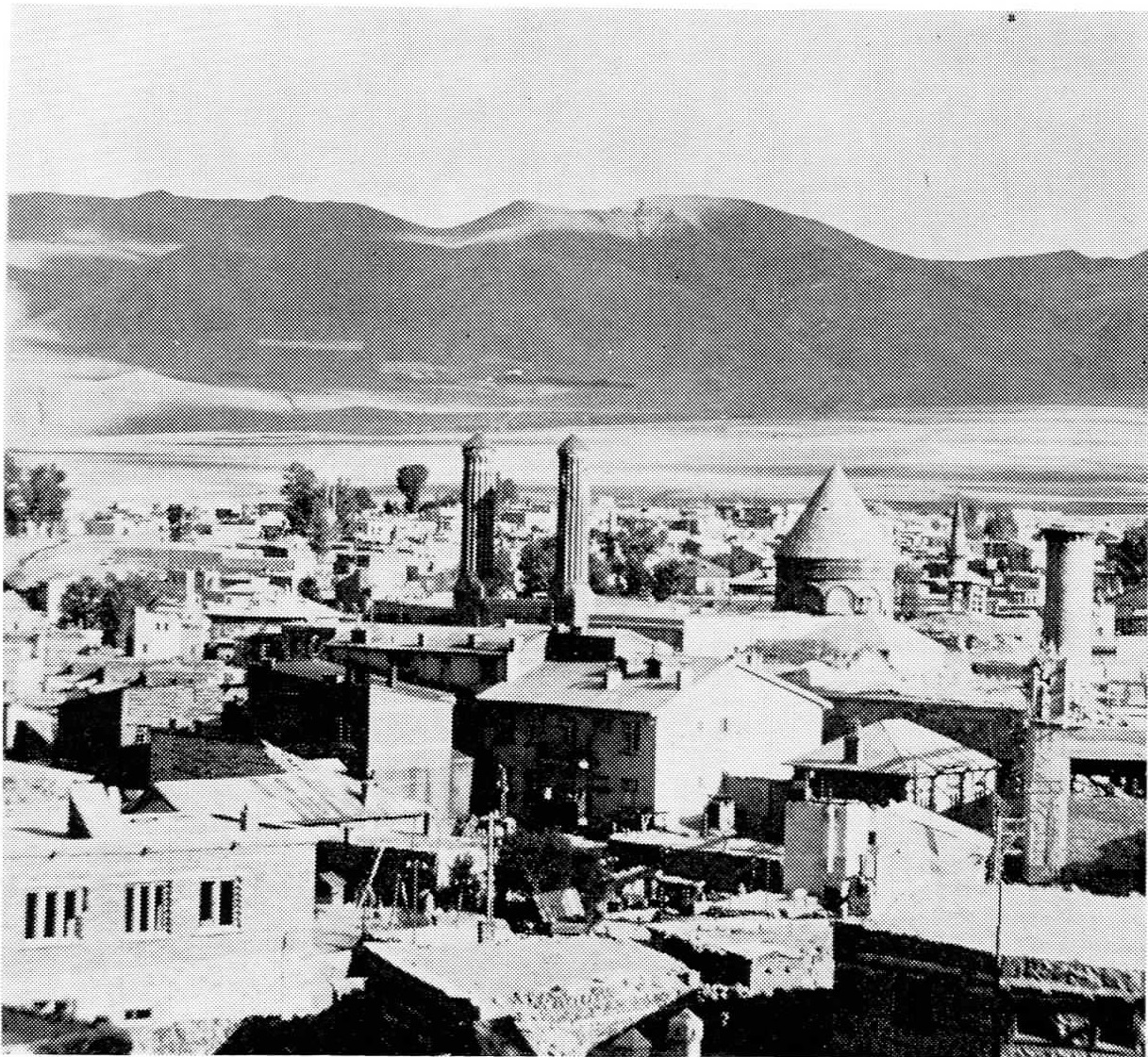

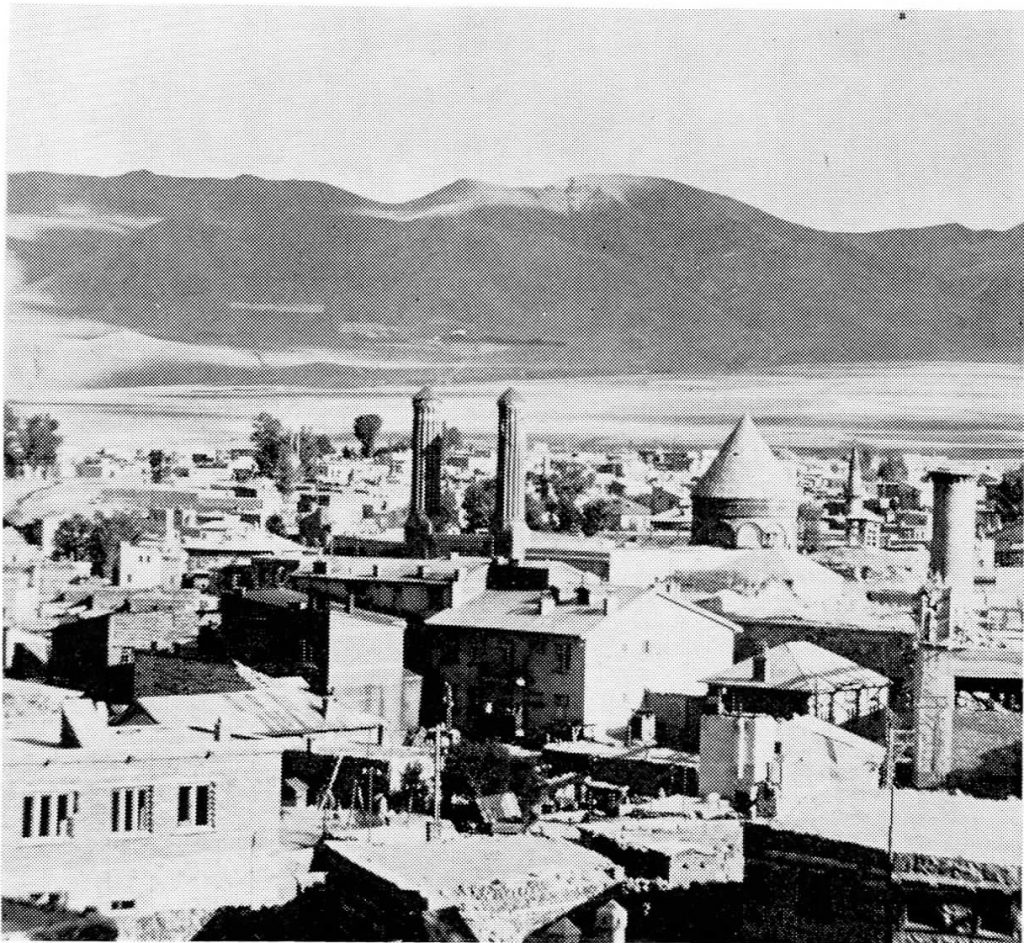

The ancient capital of Upper Armenia, Erzurum, is also the capital city of the province of Erzurum. A city with a great historical, military and cultural past, it was repeatedly renamed throughout the centuries as Garin, Garanidis, Theodosiopolis, Arzarum, Erzen- el-Rum, Erzirim, Erzeroum, and Erzurum,1 or Karin.2 Aside from national legends and traditions, we have little authentic information concerning the exact date of its founding. There is enough evidence among Assyrian inscriptions, however, to indicate <-

that the city was one of the earliest urban centers on the Armenian plateau. The historian Pliny states that: «the Euphrates rises in the Armenian Garinidis province,» and Xenophon in his Retreat of the Ten Thousand describes in detail the retreat of his armies through «the mountains of Garin and Pasen (Bassen)» about 400 B.C.

1 See N. Adonts, Hayofs Nakhararutyan Dzakume, p. 57, and Cyril Toumanoff, Studies in Christian Caucasian History, (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1963), p. 193.

2 Regarding the fortification and founding of Garin by Anthony and Justinian, see N. Adonts, Armenia in the Period of Justinian, Tr. Nina Garsoian (Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1970), pp. 113-125.

16

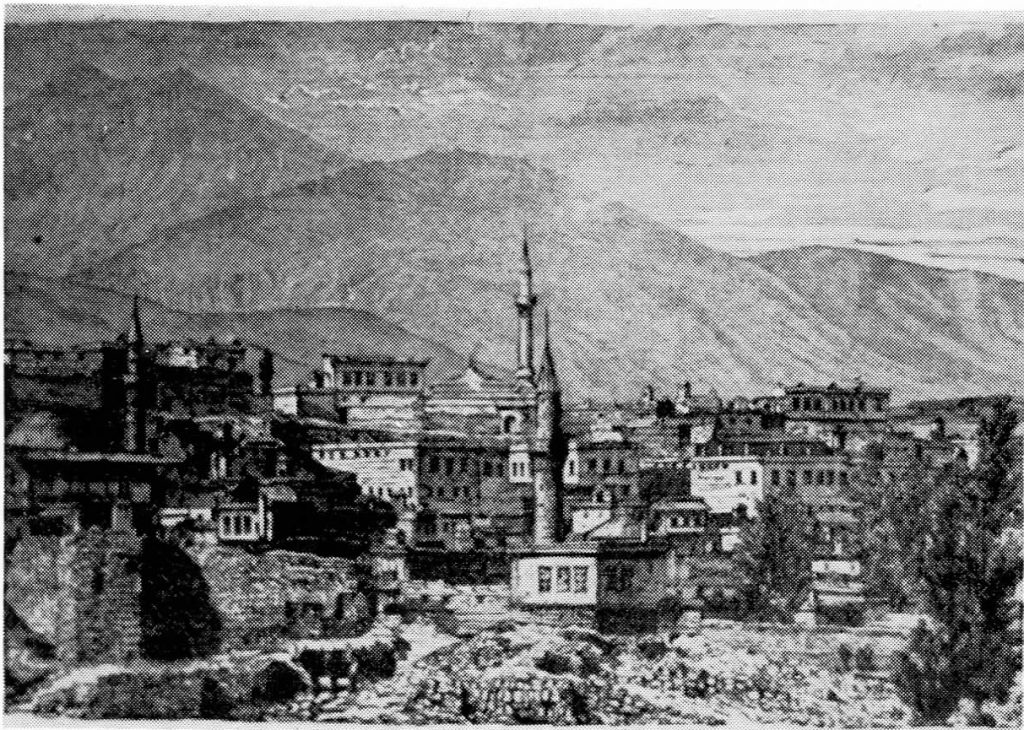

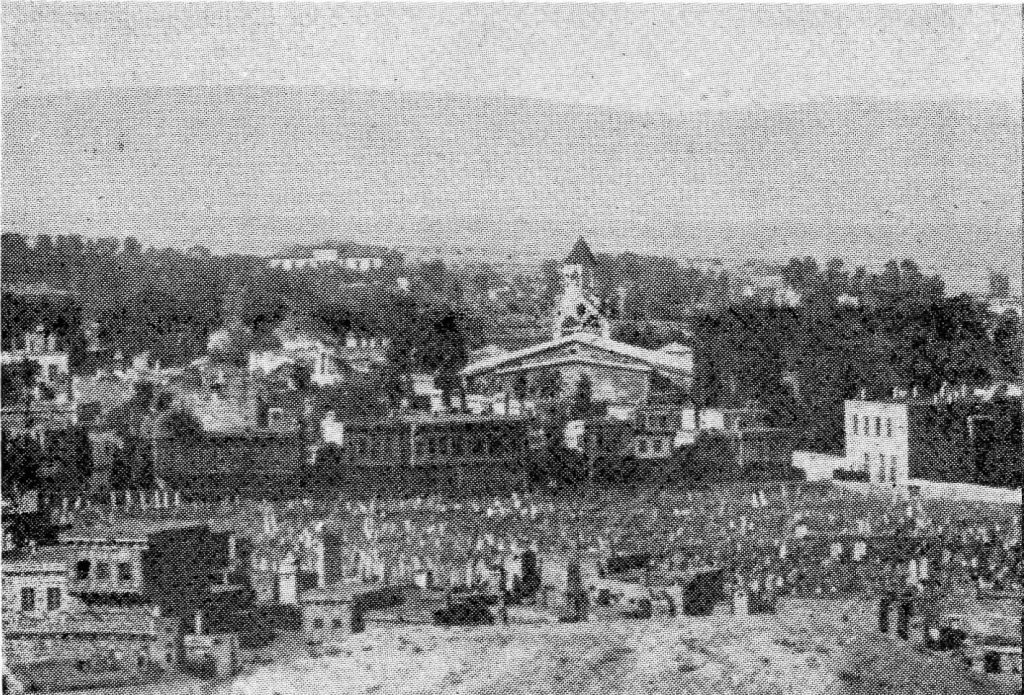

The city is located on a plateau nearly 6,800 feet above sea level. It is surrounded by thick walls which in turn are encircled by deep moats. The latter were filled with water during a siege. Erzurum has four main city gates called Gharsa Tur, Gana Tuf, Erzingu Tuf, and Tfevrizu Tuf.

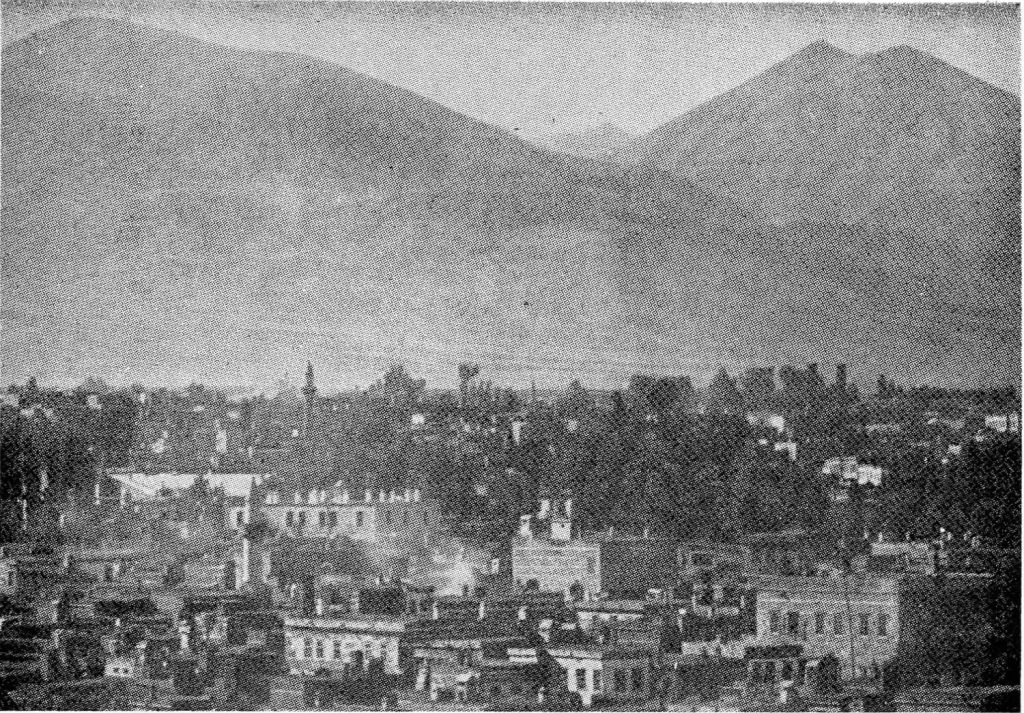

Except for the Garin plain, the city is surrounded by the mountain ranges of Ezizya, Deve Boyni, Palan Token, Bingol, Shoghagat’, and Kohanam. The distant snowcapped summit of Ararat may be seen from the latter range on clear, sunny days. Located at 39°55′ east longitude and 39°15′ north latitude, Erzurum has a temperate climate with delightful springs, pleasant summers, rainy autumns, and long, cold winters.

It has an abundance of water and hundreds of fountains. The city uses two kinds of water: one is called sari tjur (mountain water), which comes from the surrounding mountains in clay pipes, and the other is yerli tjur (local water), which flows from springs in and around the city. Each street has its continuously flowing spring water, which meets the needs of the inhabitants. However, the wealthy have their own private fountains in their gardens. The streams created by these waters eventually reach the outskirts of the city, irrigating the fields that supply the city with produce.

While a large number of ancient Christian churches were forcibly taken over and turned into mosques and public baths by the Turks, the spiritual needs of the Christian population of the city were served by a few still-surviving churches.

With the exception of such quarters as the Turkish Giavur Boghan (strangler of infidels), Demir Ayagh (iron foot), and Hollug Mahle (which had a mixed population), the streets and sidewalks of Erzurum were all stone-paved.

Besides local police stations and several huge garrisons built in different strategic positions, the city had a mighty central fortress.

Surrounded by fortified towers and solid walls, it rose over a rocky hilltop almost in the center of the city.

Ezurum had two rivulets, the Chay Ghara and Mundar Tjur running through two quarters of the same name, the first of which was used to supply the water power for many mills. There were also underground streams, the largest of which, passing under the central fortress, went to join the Garno Shamp, which the natives called Sazer.

The houses, one or two story attractive structures of stone, were

17

usually contiguous, but there were a small number of residences standing alone behind their garden walls. Every house had its guest room, sitting room, hallway, dining room, bedroom, sek’u,3 kitchen (t’ondradun), storage room (kller), toilet, granary, hayloft, stable, a yard, and often a garden.

3 A landing on the stairs large enough to be used as a family room or a play

room.

18

CHAPTER III

THE ARMENIANS OF GARIN

Your people of quality, so polite, so well-bred,

Arrayed so fine when they go promenading, Erzurum . . .

—Ashugh Tjivani

It is a historical fact that from the days of the Arsacids and Bagratids to the outbreak of World War I, the Armenians of Upper Armenia had been a sturdy people and brave fighters, attached to their country by a thousand bonds. They had possessed the qualities of industriousness, patriotism, and creativity.

Even after the loss of sovereignty, the Armenians of that region, forced for centuries to live in a state of abject slavery, never stopped rebuilding their homes and their villages, waiting patiently for the day that would bring full regeneration to their oft-ravaged homeland.

Nonetheless, there comes a time when the human capacity to endure and rebuild falters. For the Armenians of Garin that critical moment had already arrived—first in 1829 and then in 1878—when the Imperial

Russian armies conquered western Armenia only to return it to the defeated Turks shortly thereafter according to the provisions of peace treaties. Unable any longer to bear the heavy Ottoman yoke, they left their homes and villages, their farms and ploughs and retreated by the thousands (approximately 90,000) to the Caucasus with the withdrawing Russian armies.1

1 Even today, their descendants, numbering hundreds of thousands, live in southern Georgia (in Akhglkalak’ and Akhalt’skha). They still preserve the customs and traditions of their forefathers and retain their dialect. See Ely Smith and H.G.O. Dwight, Missionary Researches in Armenia, (London: 1834), pp. 65, 66, 69, 75.

19

These migrations on the one hand and the Turkish policy of forcing minority status on the Armenians in all localities on the other explain the continuous decline of the Armenian population in the province of Garin. However, until the Turkish genocide of 1915, many preferred to remain and die in their place of birth, especially since the influx of their compatriots from neighboring provinces swelled the Armenian population of the city.

These industrious, creative, and hospitable people harbored a fierce love of liberty in their bosom. Meanness and vulgarity were alien to them. Home was a kingdom, where the word of the father, mother and the eldest was like a royal decree accepted unquestioningly by the others.

The close bonds that united the members of the immediate family extended to relatives and friends. Kinsmen were more than simply relatives. They wereyVger,2 and they constituted an integral part of the physical and spiritual totality of an individual. Children were brought up in the traditional pattern. They were required not only to attend school but also to develop the qualities of courtesy, diligence, modesty, and obedience to elders.

The men devoted their time to productive labor. The women attended to the cooking, sewing, cleaning, and washing. They also had to feed and educate their children.

The Gariner knew also how to amuse himself. Baptisms, name days, pilgrimages, vacations, engagements, choosing a bride, choosing a groom, and weddings were special occasions for enjoyment and happiness. In the long winter nights, people visited their neighbors and relatives. These evenings often became festive occasions with dancing, singing, and merriment. Lastly, there were numerous public events and outdoor amusements such as concerts, public lectures, commencements, hunting, and skating parties.

The industrious and fun loving men and women of Garin were endowed with great courage. Ever ready to combat injustice and tyranny, Gariners were warmly appreciated by the entire Armenian nation.

Thus, Mampre Baleklan, a humble Armenian, could write:

From the heights of Armenia reaching heaven,

Greeting the summit of Ararat,

2 Jiger is a Turkish word meaning liver. It is often used to refer to a relative or an especially loved person.

20

You were the sentinel of our heavenly meadows,

The pride of the Armenians, city of Garin.

And our pagan deities

Who dwelt in your rocky ramparts

Eternally sent out an invincible will

To our heroic warriors.

And when your temples ofVahakn and Anahid

Vibrated with Armenian melodies and hymns,

Your warriors, enthused with the new

Enlightened religion, threw themselves down at Avarayr.

And when the sun of the Armenians was extinguished and darkness

descended,

Our fathers created a new center of light—

Sanasarian-whose new educators lit the torch of learning

And carried it to all corners of our paternal land.

And the day came when voices echoed from the lofty mountains of

Garin,

Filling the hearts of freedom-lovers everywhere,

Followed by suffering, war, death, and massacre-

Till the sun of Free Armenia shone again.3

The Gariner had an extremely high standard of moral values.

Marriage was a sacred union, and as such it was indissoluble until death. Divorce was a rarity (decades passed without a single case), and adultery was punished by death. This is all the more remarkable in the light of the moral code which prevailed in the Turkish segment of the population.

3 Meshag (Fresno, California: January 1950).

21